Every abstraction you introduce is a set of rules in disguise. A class, a module, a function, a service boundary — each one silently declares: here’s what you can do, here’s what you can’t, and here’s why.

The sign of a mature design is that you can explain those rules in a sentence or two. Not because the problem is simple — but because the solution has been distilled to its essence.

Try it. Pick any structure you’ve recently introduced. Explain its rules to a colleague in plain language. If the explanation is short and clear, you’ve likely arrived at a good design.

If you can’t — if the explanation sprawls, if it requires caveats upon caveats, if the listener’s eyes glaze over — that’s not a communication problem. That’s a design problem.

And it usually means one of three things happened.

A hacky solution was implemented

The rules are hard to explain because they aren’t real rules — they’re side effects of a shortcut. “Well, you can’t call this before that, because internally we’re reusing a buffer that gets initialized on the first call, and if you…” — stop. That’s not a rule. That’s an implementation leak dressed as a contract.

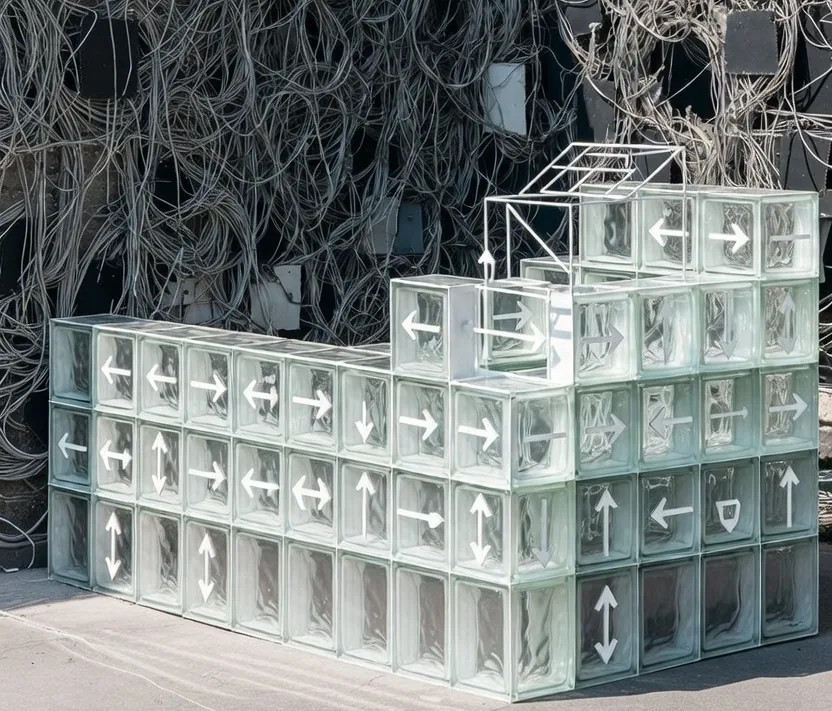

Hacks produce temporal rules: order dependencies, initialization sequences, hidden state mutations. These rules feel complicated to explain because they don’t model anything real. They model the path of least resistance someone took at 11 PM on a Friday. The nest of accidental complexity.

A rule that needs three paragraphs to explain is a rule that will be problematic. It’s only a matter of time. It will create friction in the wrong places, it will stop enabling you to grow when you’ll need it most.

A can of worms was accepted

Sometimes the rules are hard to explain because the problem space was never properly bounded. You accepted a requirement that seemed small but carried exponential accidental complexity beneath the surface. Now your abstraction has seventeen configuration options, four modes, and a matrix of valid combinations that A) nobody can hold in their head B) are failing to capture the spirit of the narrative of the UX they are supposed to produce.

The rules are complicated because the scope was never challenged or the abstractions are drafty, immature. Good design can have essential complexity, but that demands time, deep thinking, and maturing how the abstractions make the narrative flow. “Can it also handle…?” was answered with “sure” too many times, too soon, in too unconsequentialist a fashion — and now you have a half-working Swiss Army knife that can shoot you in the foot in a combinatorial explosion of seventeen parameters. Functional elegance went down the drain.

When you can’t explain the rules, ask yourself: did I accept complexity I should have refused?

Did I think about them in slow motion, deep enough? Enough times? When did I give the universe a chance to inspire me about the edge cases and subtleties around its dynamic behavior? Under heavy load? Under malformed state?

Saying no to a requirement is sometimes the most important design decision you’ll make.

An elegant design was rejected

This is the most painful one. Sometimes a clean, simple design existed — one where the rules would have been self-evident — but it was rejected. Too “academic.” Too much refactoring. Too risky to change the existing structure. Too expensive for this sprint.

The right structure wanted to exist but nobody gave it a chance.

So you bolted the new behavior onto the old structure, and now the rules are a patchwork of the original intent and the compromises that followed. The explanation is long because you’re narrating a history of decisions, not describing a coherent design that implemented a coherent story. Technicisms hijacked the UX story — and injected friction into the users’ and operators’ journeys.

Every time you explain rules by telling a story — “well, originally this was X, but then we needed Y, so now Z” — you’re confessing that the design was never unified. You aren’t stating rules. You’re reciting scars.

These three failure modes look different on the surface, but they share a root cause: the design was allowed to grow around the problem instead of through it.

The problem didn’t get the love it desperately needed.

The solution got too much emotional attachment too soon.

Rules are the interface between your design and everyone who will ever use it. Including future you. Including the AI that will generate code against it next month. If those rules are simple, your design can be extended, tested, and reasoned about. If they’re complex, every future change carries compounding risk that remains silent until something breaks.

Mature design doesn’t mean fewer features. It means the features that exist have rules so clear they barely need documentation because they feel natural for the users’ journeys.

The question isn’t whether your code works.

The question is: can you explain its rules?

Can you take good care of them long term?

If you can’t, you already know what to fix — you just need to exercise the muscle of expressing it.